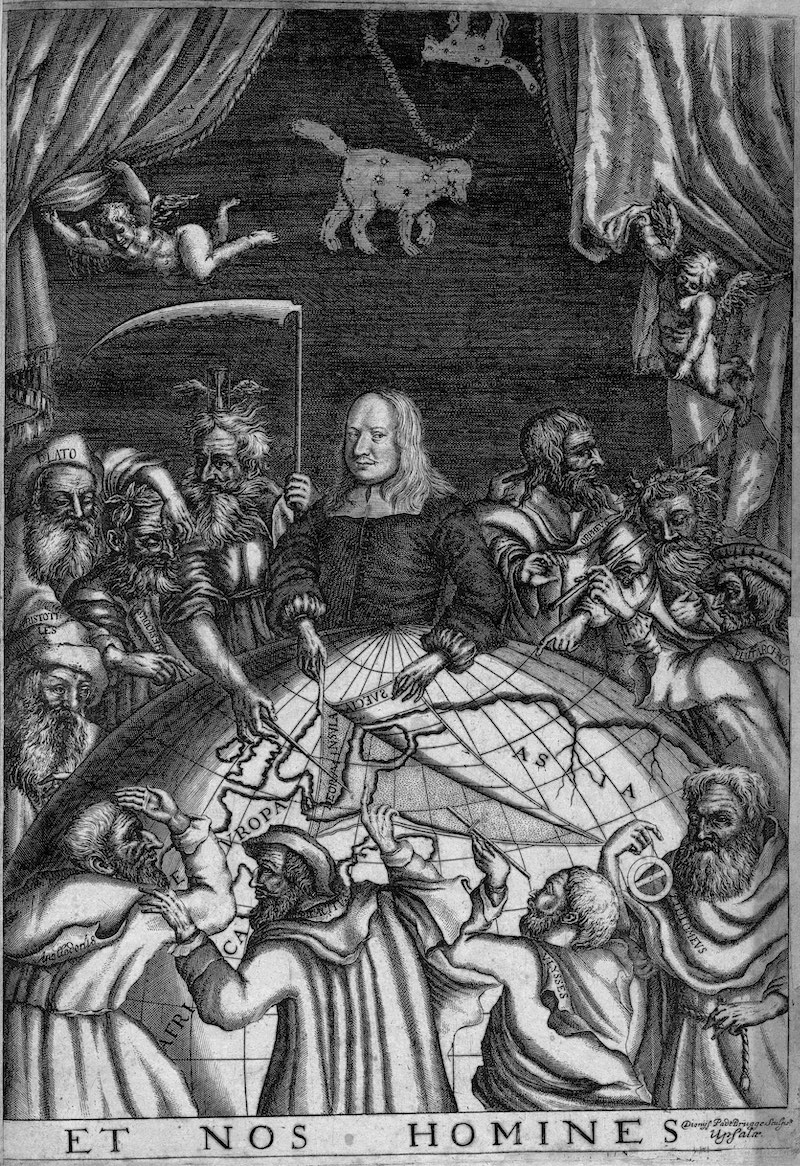

Two putti introduce the scene that opens the Atlantica’s volume of plates.

Hovering over the stage, they pull aside the thick curtains revealing three constellations – the two bears, Ursa Minor and Ursa Major, and a few stars above them hinting at the tail of Draco.

We find ourselves under a northern sky, the stars imply.

The northern hemisphere of a voluminous globe dominates the lower half of the frontispiece. At the center of the scene stands a man with shoulder-length hair, dressed in 17th-century garb, the North Pole at his navel. Wielding a scalpel in his right hand, he draws it across the Scandinavian Peninsula. With his left, he peels back a section of the outer layer, inscribed Svecia (Sweden), revealing the Insula Deorum – The Island of the Gods – lying below.

The man wielding the scalpel is Olof Rudbeck, a professor at Uppsala University and Sweden’s leading anatomist. In 1679, he published the first volume of his Atlantica – a monumental work declaring Sweden to be the cradle of our most ancient myths.

To Rudbeck’s left we see a figure with scythe and hourglass, the classical iconography of Kronos (Father Time). With his right hand, the old man points out the flayed part of the globe to three persons to his left. The names inscribed on their hats and robes reveal the bearded men to be the poet Hesiod and the philosophers Plato and Aristotle.

Time has revealed the truth these Greek writers hadn’t seen, the arrangement tells us.

The figures to the right of Rudbeck and in front of the globe reiterate the message. We see ancient historians, geographers and legendary travellers – Orpheus, Ulysses, Plutarch, Ptolomaeus, Tacitus, Apollodorus. They all are witnesses that Rudbeck made speak for his case in his Atlantica. Some of them analyze the truth he uncovered using scientific instruments. Others express awe and surprise as the insight sinks in.

We must have been blind to not see this truth, their gestures imply.

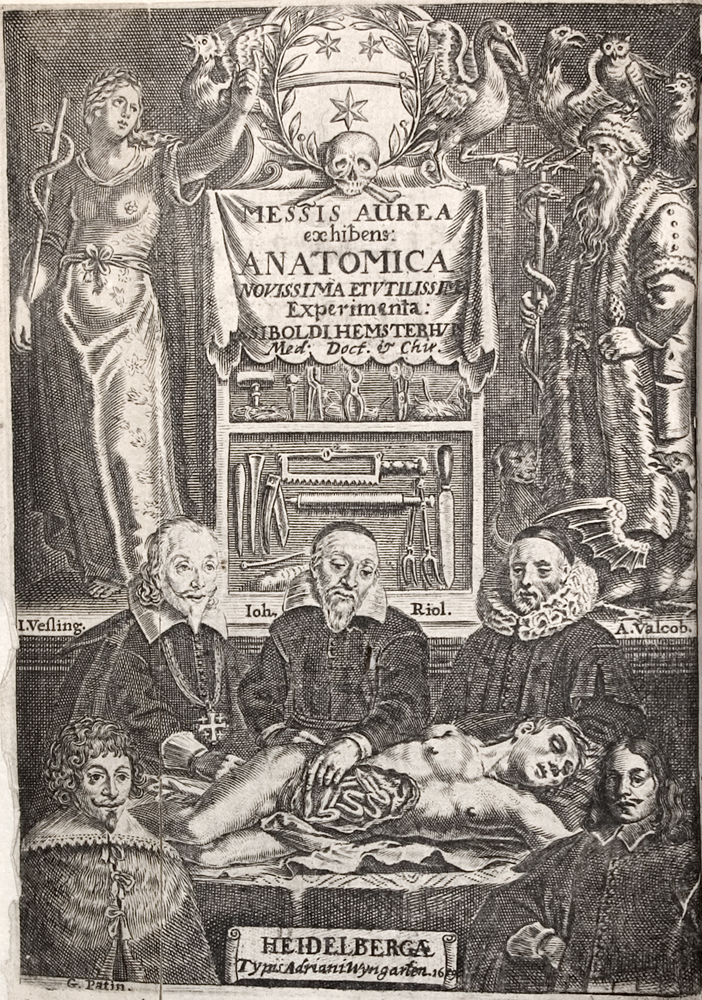

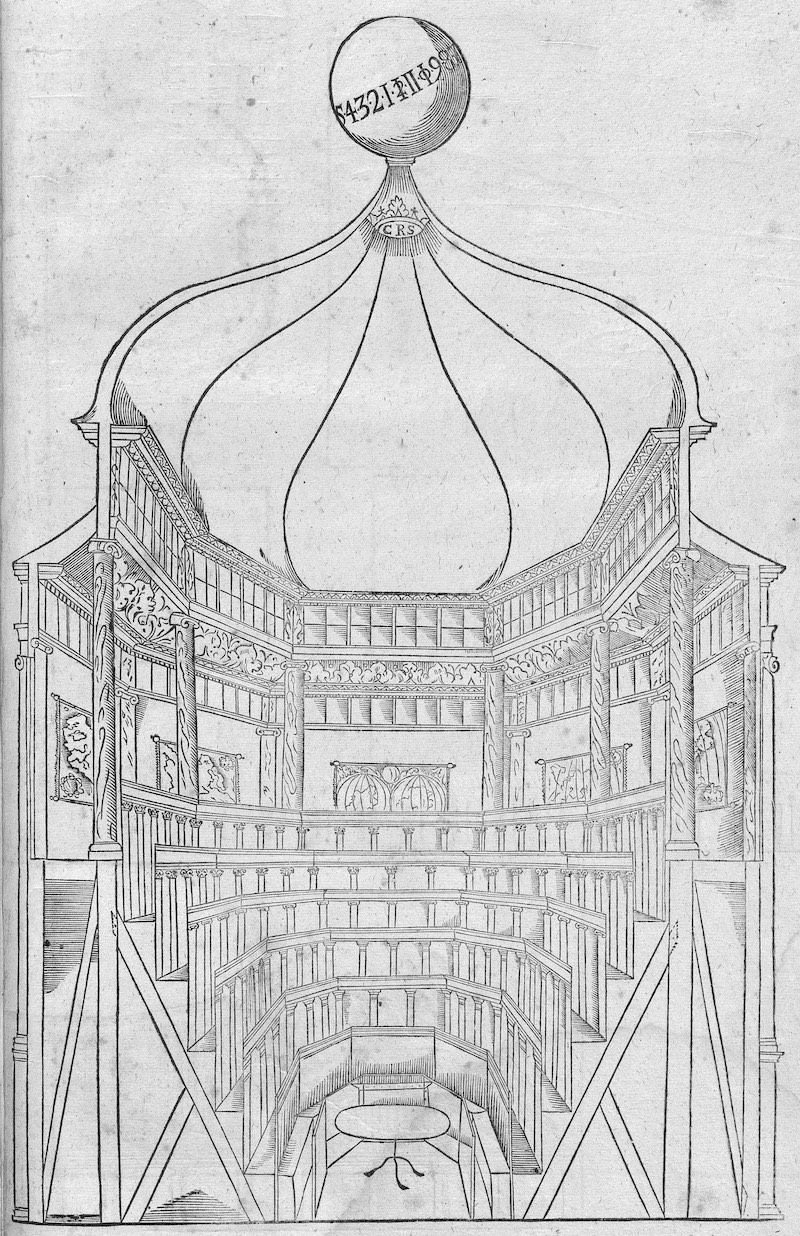

The programmatic engraving by the artist Dionysius Padt-Brugge draws inspiration from the frontispieces of medical works of the time. They showed anatomists located at the center of anatomical theatres, demonstrating to students on the crowded tiers above the nature of the human body.

Typical for the early modern age, these academic institutions pursued a scientific practice inspired by autopsy and observation. These values informed Rudbeck’s practice as a professor of anatomy, famous across Europe for having discovered the lymphatic system.

It was these same values that informed the quest for Atlantis in Sweden that Rudbeck pursued over the last three decades of his life. As an antiquarian/historian, he had his students dig around the country’s oldest buildings, or sent out expeditions to gather measurements of the kingdom’s highest peaks in order to compare them with the ancient writings.

At Uppsala, Rudbeck himself was both the architect and the main player of the anatomical theatre. In the same way, he stands center stage in the Atlantica’s frontispiece.

Et nos homines – ‘We, too, are humans’.

The Latin quotation at the bottom of the frontispiece hints at the impetus behind Rudbeck’s three-decade long project. The Atlantica is an expression of Sweden’s desire to join the ranks of established national cultures in Europe. Yet the work went beyond filling in the blanks of the kingdom’s early history.

With the publication of the Atlantica, Sweden burst onto the scene not as an equal, but as the apex civilization that had brought forth all culture in Europe.

Raise your heads to the north if you seek for the site that inspired our oldest myths – this was the message of the Atlantica’s frontispiece for an international audience.