The Atlantica was not the only project that Rudbeck pursued in the final decades of his life.

Around 1700, he was working on a heavily illustrated botanical work called the Campus Elysii (‘The Elysian Fields’). This atlas of plants – produced with support of the crown and his entire family – intended to present all botanic specimens known at the time using thousands of woodcut illustrations.

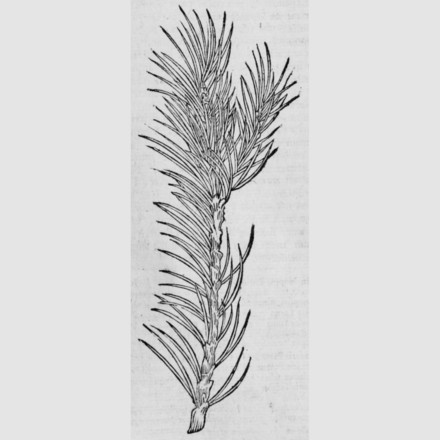

Botanical woodcuts recur within the volumes of Rudbeck’s Atlantica. The third one (1698) includes a set of nine which all show twigs of conifer trees.

Rudbeck used these illustrations to solve an unanswered riddle from a passage in Pliny Natural History. The ancient Roman encyclopedist had written about Mount Atlas, a site traditionally associated with Northern Africa.

The Atlas range was one of the many disputed sites from classical mythology that Rudbeck was eager to claim for Sweden. Botany should now prove him right.

The slopes of Mount Atlas, so Pliny wrote, are

filled with dense and lofty forests of trees of an unknown kind, ... with very tall trunks remarkable for their glossy timber free from knots, and foliage like that of the cypress ...PLINY, Natural History, V.1

Which ‘cypress-like’ tree could the Roman have had in mind? Rudbeck’s trail of evidence began with a woodcut showing a cypress twig.

This tree, the versed botanist remarked, features comparitvely small needles, measuring only half a finger in length. With the help of further illustrations, Rudbeck ruled out possible candidates for Pliny’s conifer. All of their needles were simply too long to qualify as contenders, he argued.

Yet there was one tree in the North, he argued, that fit the Mediterranean author’s description. The needles of this tree are of a size comparable to those of the cypress. Its branches also start shortly above the ground. And both trees grow in a narrow, cone-shaped form.

The tree that Pliny described, Rudbeck explained, had to be the one that grows all across the entire Swedish-Norwegian mountain ridge, flourishing well beyond 64° latitude where it forms ‘dense and lofty forests’ capable of carrying the load of a harsh winter every year. To any Swede, the answer to Pliny’s riddle must seem short and simple – it just had to be ‘our spruce’.

^ botanical work called the Campus Elysii: Two volumes of this work were printed (see volume 2 on alvin-portal.org) before the Great Fire of Uppsala destroyed thousands of woodcuts for the remaining volumes.

^ the answer to Pliny’s riddle must seem short and simple – it just had to be ‘our spruce’: The line of argumentation is developed in Rudbeck, Atlantica, vol. 3, p. 573.