On a stone there is a poem

that is written in runic script.

The poem was not put there yesterday.

Between Norway and Jämteland,

it has been read by many women and men ... From the song of the Stone of the Green Valley (stanza 7)

The song is more than five centuries old. In Old Swedish, it tells of a stone in a Grön Dal, a Green Valley located in Sweden’s far north, between Jämtland and Norway. According to the song, a runic inscription on the stone’s surface holds a dramatic prophecy: When this stone falls, the world as we know it will come to an end.

The legend of the stone became a subject of fascination for antiquarians in the decades around 1600, when scholars such as Ole Worm and Johannes Buraeus made efforts to find it.

Perhaps Olof Rudbeck had this tune in mind when he himself sent out an expedition into the mountains of Jämtland, Dalarna, and Härjedalen. In 1675 his men returned to Uppsala with drawings of mountain panoramas and the sketch of a stone located some kilometers north of Storlien in western Jämtland, within sight of the Norwegian border.

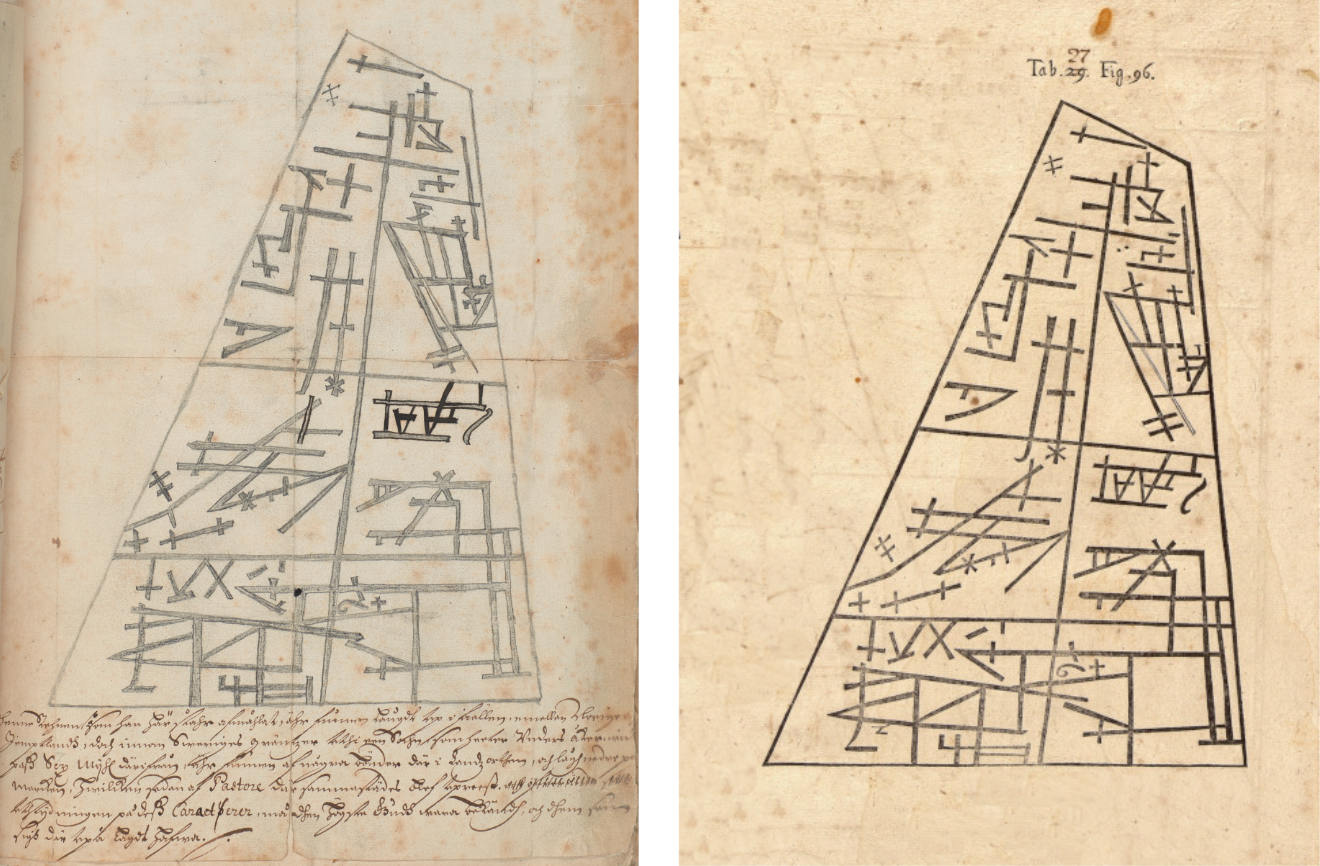

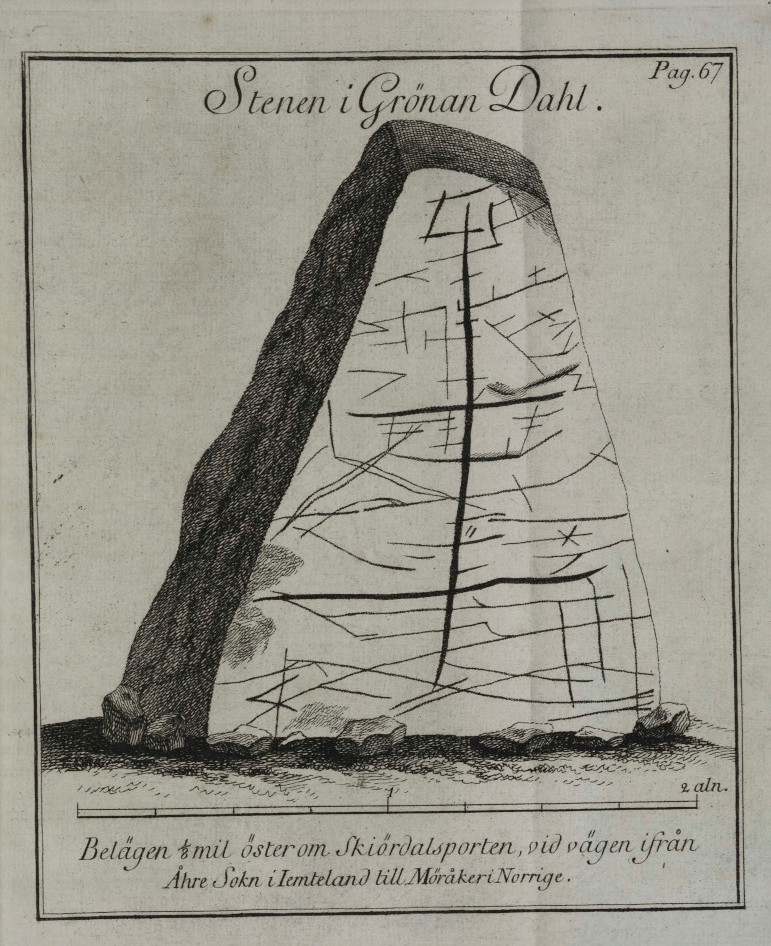

The drawing of the stone from the north – today held at the Royal Library in Stockholm – is attributed to Samuel Otto, one of the participants in Rudbeck’s expedition. It is the earliest known depiction of the stone. Four years after the expedition returned, a woodcut of the drawing was used as an illustration in Rudbeck’s Atlantica.

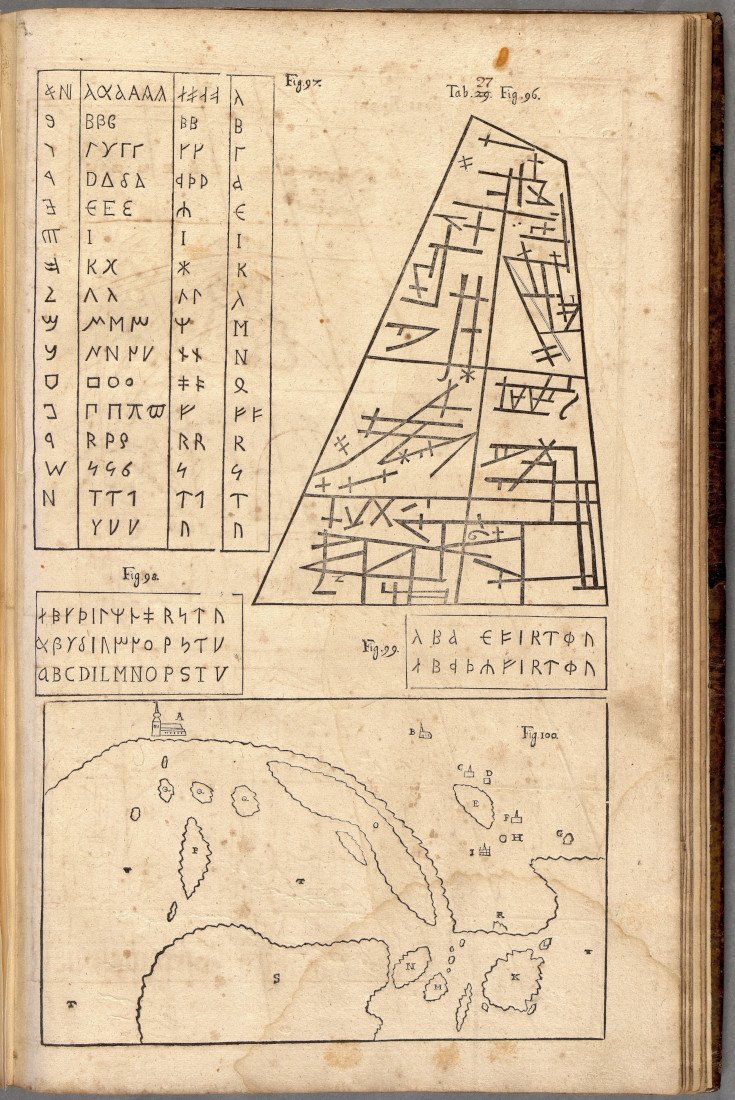

What the stone itself actually meant for Rudbeck, however, remains an unanswered question. In its thousands of pages, his Atlantica never once refers to the illustration that he placed next to charts comparing the Phoenician, Greek, Gothic and runic alphabets.

Did Rudbeck see a link between the shapes of these letters and the enigmatic etchings on the ancient stone? We can only speculate about what the Uppsala polymath had in mind for the stone. Perhaps the answer went up in smoke in 1702 with the fourth volume of the Atlantica.

If Rudbeck’s Atlantica was the first book to publish an illustration of the stone, it was another work from the same era that tied the ancient tune about the Stone in the Green Valley to the enigmatic object located on the Norwegian border.

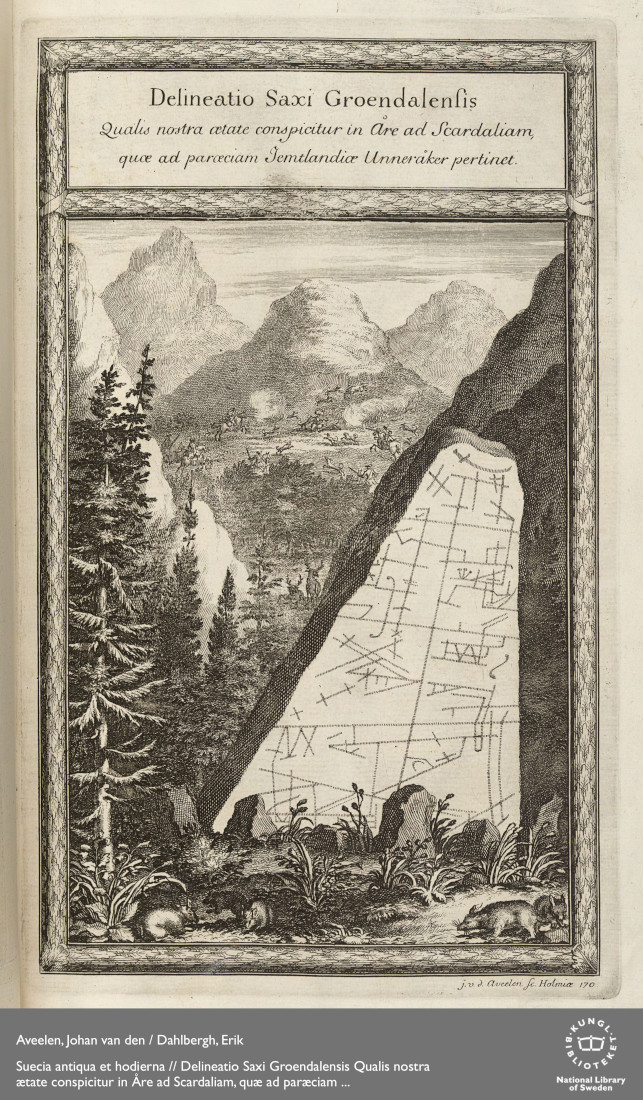

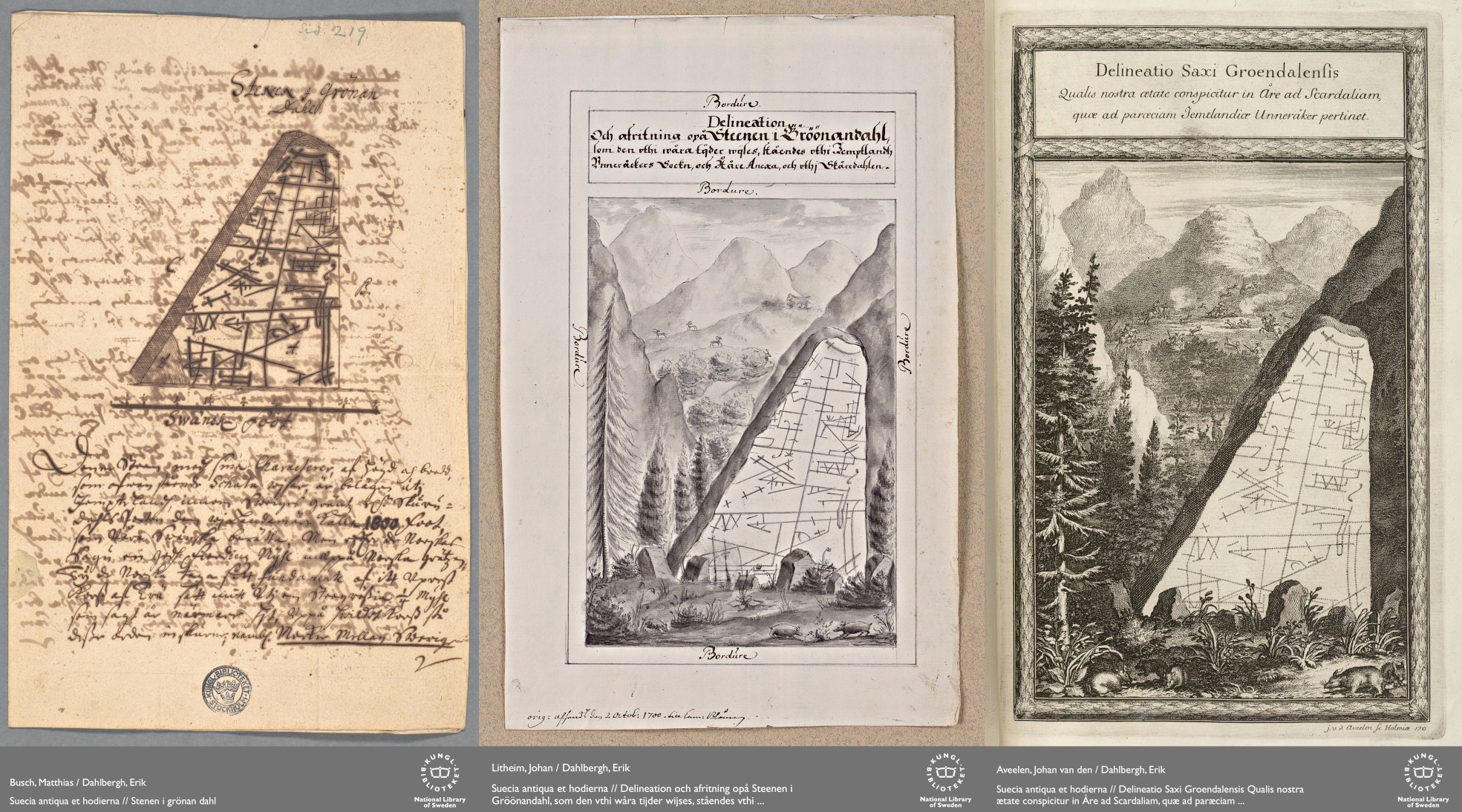

Around the same time as Rudbeck was writing his magnum opus, the artist Erik Dahlberg was working on a project of similar breadth. It its final version, his Suecia Antiqua et Hodierna (Ancient and Modern Sweden) featured 353 lavish copperplate engravings of cities, palaces, and antiquities all across Sweden. Among the illustrations was the same stone depicted in the Atlantica. In Dahlberg’s version, it was titled ‘Stone in the Green Valley’.

Dahlberg’s choice of title for the engraving – a direct reference to the ancient song – inextricably tied the antiquity from the north to the tune and its prophecy.

In the engraving the stone is seen in a mountainous landscape – a landscape that turns out to be purely fictitious.

Dahlberg himself had never travelled to Jämtland. The depiction of the stone in his book is based on a sketch from 1700 which was sent to him by Matthias Busch, a land surveyor in Norrland. One of the artists Dahlberg employed then copied this sketch for the drawing which would be used for the final engraving, placing the stone in a landscape that combined elements generally associated with Sweden’s North (mountains, reindeer, lemmings).

The landscape where the stone is actually located is a far cry from the mountain idyll envisioned by Dahlberg’s artist. It stands next to a lake along the old pilgrim’s path from the Baltic coast to Trondheim, not far from the Norwegian border (Skurdalsporten), where the terrain is relatively flat and covered with shrubs.

The stone has yet to give up its secret.

Over the centuries, scholars have proposed numerous interpretations for the stone – a border marker, a pilgrim’s waystone, writings in an unknown alphabet or patterns related to the iconography found on Sámi drums, or even a forgery based on the sketch in the Royal Library, created by Rudbeck’s expedition in order to buttress ideas that never materialized.

Not all visitors to the stone were spurred to flights of fancy. Among the carvings that visitors left on the reverse side of the stone is a coat of arms, carved by the Swedish mineralogist Daniel Tilas in 1742.

Tilas printed a new illustration of the stone in a geological handbook he published two decades after his visit. He was well aware of the ancient prophecy and the earliest depictions of the stone. His interpretation, however, was much more sober.

The stone – which he found lying flat and re-erected, a tongue-in-cheek assurance that prophecy would not be fulfilled – was on a green plain, not in a valley. According to Tilas, both Rudbeck’s and Dahlberg’s illustrations had exaggerated the regularity of the lines. He saw nothing special in them, and was convinced they were nothing more than cracks in the stone, simply a natural phenomenon.

Generations of scholars had just seen what they wanted to see. Rest assured, my dear antiquarians, Tilas concluded, that this region holds enough ‘Stones in the Green Valley’ for all the world to have one.

As an introduction to the rich literature on the stone see Axel Nelson, "Samuel Otto och Olaus Rudbecks Atlantica. Ett bidrag till Lapplandsforskningens äldre historia", Kungliga Humanistiska Vetenskaps-Samfundet i Uppsala Årsbok (1943), pp. 56–88.

The song of the Stone in the Green Valley began circulating in the 16th century and versions were later collected and printed (with notes and an introduction detailing its history) as part of E.G. Geijer and A.A. Afzelius, Svenska Folkvisor, ed. R. Bergström and L. Höijer, Stockholm, 1880, no. 106.

^ Rest assured, my dear antiquarians: Paraphrase of a quote by Daniel Tilas, Utkast til Sveriges mineral-historia, Stockholm, 1765, p. 67.